At the edge of Mombasa’s Old Town, where the Indian Ocean breeze carries the scent of cloves and salt, Fort Jesus rises from coral rock as a four-century-old sentinel. Built by the Portuguese in the late 16th century, it remains one of the most powerful symbols of East Africa’s place in the global currents of commerce, conquest, and culture.

But Fort Jesus is only one outpost in a long chain. Across today’s Kenya, Tanzania, and Zanzibar, forts, mosques, palaces, and stone towns record the rise and fall of the Swahili Coast a cosmopolitan world where Africa, Arabia, India, and Europe were bound together by the Indian Ocean trade.

A Crossroads of Maritime Worlds

From the 8th–10th centuries, small Swahili settlements grew into thriving ports. Seasonal monsoon winds carried dhows across the ocean, linking the African interior to Arabia, Persia, and India. Outbound commodities included gold from the Great Lakes and Zimbabwe plateau, ivory, timber, rhinoceros horn, and aromatic resins. In return came Chinese porcelain, Indian cotton textiles, Arabian incense, and glass beads that entered East African ritual and decorative traditions.

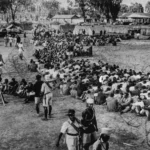

The same networks that brought wealth also carried enslaved people. From at least the 10th century but accelerating in the 18th and 19th centuries, caravans brought captives from as far inland as present-day Congo, Zambia, and Malawi to coastal entrepôts such as Bagamoyo and Kilwa. From there, they were shipped across the Indian Ocean to Arabia, Persia, and the Indian subcontinent. This traffic profoundly shaped coastal fortunes, fortified architecture, and the lived experience of communities.Chronology of Power Shifts

- 1498: Vasco da Gama lands on the East African coast, marking Portuguese entry.

- 1593–1596: Construction of Fort Jesus in Mombasa by Giovanni Battista Cairati, solidifying Portuguese military presence.

- 1698: After a 33-month siege, Omani forces expel the Portuguese from Mombasa, inaugurating Omani ascendancy.

- 18th–19th centuries: The Omani Al Bu Sa‘id dynasty relocates its capital to Zanzibar, making it the hub of spice and slave trades.

- 1895 onward: British protectorates consolidate power over coastal Kenya and

Tanganyika, repurposing forts as prisons, barracks, and administrative centers.

This sequence helps explain the layered architecture and cultural influences visible today.

Key Sites and Their Stories

Fort Jesus, Mombasa (Kenya)

- Built 1593–1596; designed to Renaissance geometric principles with bastions, casemates,and embrasures, but constructed in coral rag and lime mortar by local labor.

- Changed hands nine times between Portuguese, Omani, Swahili, and British control.

- Today: a UNESCO World Heritage Site and museum showcasing finds such as Ming,porcelain shards, Portuguese coins, and local ceramics.

Kilwa Kisiwani (Tanzania)

- Flourished between 12th–15th centuries; dominated southern coastal trade in gold, ivory, and enslaved people.

- Notable monuments: the Great Mosque (among the oldest in Africa), Husuni Kubwa palace, and the Portuguese Gereza fort.• Excavations by Neville Chittick (1960s) revealed Chinese porcelain and Persian wares, demonstrating Kilwa’s integration into global commerce.

- UNESCO site; ongoing conservation against erosion and salt crystallization.

Lamu Fort & Old Town (Kenya)

- Constructed 1810–1823 with Omani patronage; later used by the British as a prison.

- Anchors Lamu Old Town, a living Swahili settlement with carved mangrove doors,rooftop barazas, and active mosques.

- Archaeological surveys uncovered imported ceramics and locally crafted jewelry,attesting to centuries of trade.

Bagamoyo (Tanzania)

- 19th-century entrepôt for ivory and enslaved people; caravans ended here before export to Zanzibar and beyond.

- Surviving sites include German boma, old mosques, and coastal tombs.

- Today: cultural capital with Bagamoyo Arts College; memory of the slave trade remains central to interpretation.

Other Key Sites

- Stone Town, Zanzibar: Omani-built Old Fort (Ngome Kongwe), today a cultural venue.

- Gede Ruins, Kenya: A forest-shrouded 12th–17th century town, excavated in the 1920s; yielded beads, Chinese celadon, and Venetian glass.

- Pate Island: Important medieval settlement, remembered in oral poetry and tomb inscriptions.

Architecture and Cultural Fusion

Builders blended Portuguese bastion geometry with local coral-rag masonry, Swahili carpentry, and imported materials. Bastions, powder magazines, and embrasures stood beside carved wooden doors, plaster niches, and Arabic inscriptions.

Domestic contexts unearthed at Kilwa, Lamu, and Gede reveal Chinese porcelain bowls, Persian silk fragments, and Indian cotton cloth, demonstrating cosmopolitanism in everyday life.

Conservation, Community, and Threats

Many sites survive due to custodianship by national museums, UNESCO monitoring, and local community groups. At Fort Jesus and Lamu, education programs bring schoolchildren to learn Swahili heritage. In Kilwa, shoreline stabilization projects reduced its UNESCO “in danger” status.

Yet threats mount:

- Rising sea levels and storm surges erode foundations.

- Salt crystallization within porous coral stone accelerates cracking.

- Vegetation overgrowth undermines walls.

- Funding gaps stall long-term conservation.

Urgent interventions include controlled vegetation removal, community-led masonry repair, and tourism-funded maintenance programs.

Human Impacts and Local Voices

For coastal communities, these forts are not just relics. They are:

- Sources of livelihood: guides, artisans, hoteliers, and custodians earn from heritage tourism.

- Sites of memory: oral traditions recall sieges, migrations, and enslavement.

- Cultural classrooms: school trips, festivals, and performances animate old spaces.

Tensions remain — tourism revenue does not always flow evenly, and local custodians sometimes lack decision-making power. Strengthening community participation remains central to sustainable conservation.

Access, Safety, and Logistics

- Best time to visit: June–October and December–February (cooler, dry).

- Fort Jesus (Kenya): Open daily; small entry fee; guides available. Combine with Mombasa Old Town.

- Kilwa Kisiwani (Tanzania): Reach by dhow from Kilwa Masoko; visitors must hire licensed local guides; bring water and sun protection.

- Lamu (Kenya): Accessible by air from Nairobi or Mombasa; safe walking tours through Old Town; donkey transport common.

- Bagamoyo (Tanzania): About 75 km north of Dar es Salaam by road; local museums and cultural centers open daily.

Always check foreign travel advisories, hire registered guides, and respect local customs when photographing religious or community spaces.

Why They Matter

The coastal forts are guardians of memory and identity. They remind us that East Africa was not a periphery but a vital node in world history where Swahili elites, Portuguese captains, Omani governors, and British administrators contested, collaborated, and left enduring marks. They also bear the weight of more difficult legacies: the slave trade, forced labor, and colonial exploitation. Facing these truths openly, while celebrating the resilience of Swahili culture, makes visiting these sites both sobering and inspiring.

Suggested Sources for Deeper Reading

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre dossiers on Fort Jesus, Lamu Old Town, and Kilwa Kisiwani.

- Neville Chittick, Kilwa: An Islamic Trading City on the East African Coast (1974).

- James de Vere Allen, Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture and the Shungwaya Phenomenon (1993).

- Prita Meier, Swahili Port Cities: The Architecture of Elsewhere (2016).

- National Museums of Kenya and Tanzania Antiquities Division websites.

Closing Reflection

Standing inside Fort Jesus as waves crash against coral stone walls, or walking Kilwa’s silent ruins beneath the flight of seabirds, one confronts both the grandeur and the grief of East Africa’s coastal history. These sites are living classrooms of global history, where trade, slavery, architecture, and community resilience converge. To preserve them is to honor the past while sustaining futures rooted in knowledge, memory, and pride.

Related Posts

-

Riding the rails: Kenya’s SGR and the future of east

Dawn at Nairobi Terminus At 6:00 a.m., the cavernous hall of Nairobi Terminus hums with…

-

Luka wa Kahangara: The Chief at the Heart of the Lari Massacre

In the misty highlands of Central Kenya, the early 1950s were years of land hunger,…

-

The Battle of Isandlwana and the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879

At eleven o'clock on the morning of 22 January 1879, a troop of British scouts…