The transatlantic slave trade not only distorted Africa’s economic development, it also distorted the view of the history and significance of the African continent itself. It is only in the last fifty years that it has been possible to correct this distortion and begin to restore Africa’s rightful place in world history.

The African continent has been recognised as the birthplace of humanity and the cradle of civilisation. We still marvel at the great achievements of Kemet, or Ancient Egypt, for example, one of the most remarkable of the early African civilisations, which first developed in the Nile Valley over 5,000 years ago.

Even before the rise of Kemet, however, it seems likely that an even older kingdom, known as Ta Seti, existed in what is now Nubia in Sudan. This may well have been the earliest state to exist anywhere in the world. Africa can therefore be credited not only with giving rise to the many scientific developments associated with Egypt, engineering, maths, architecture, medicine, etc. but also with important early political developments such as state formation and monarchy. This shows that economic and political development, as well as scientific development, during this early period, was perhaps more advanced in Africa than on other continents.

The African continent continued on its own path of development, without significant external intervention until the fifteenth century AD. Some of the world’s other great civilisations, such as Kush, Axum, Mali and Great Zimbabwe, flourished in Africa in the years before 1500. In this early period, Africans participated in extensive international trade networks and in trans-Oceanic travel. Certainly, some African states had established important trade links with India, China and other parts of Asia long before these were disrupted by European intervention.

A North African conquest of the Iberian Peninsula began in the 8th century and led to the occupation of large parts of Spain and Portugal for several centuries. This Muslim invasion reintroduced much of the knowledge of the ancient world to Europe and linked it much more closely to North and West Africa. It was gold from the great empires of West Africa, such as Ghana, Mali and Songhay, that provided the means for the economic departure of Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries and piqued the interest of Europeans in western Africa. In fact, it was the wealth of West Africa, especially as a source of gold, that encouraged the voyages of the early European explorers.

In the 15th century, the African continent was already one of great diversity. The existence of great kingdoms and empires, such as Mali in the west and Ethiopia in the east, were in many ways exceptional rather than typical. In many parts of the continent there were no large centralised states, and many people lived in societies where there was no great distribution of wealth and power. In such societies, there were generally more democratic systems of governance by councils of elders and other kinship and age-based institutions. As a consequence, there was also a diversity of religious and philosophical beliefs. In many areas, these beliefs remained traditional and emphasised the importance of communicating with common ancestors. The Ethiopian Empire was unusual because the Orthodox Christian Church, which was of ancient origin in that region, had increasingly important state functions. In Mali, and in some other areas of western and eastern Africa, as well as throughout North Africa, Islam had already begun to play a significant role before 1500. Most importantly, African societies followed their own patterns of development before the onset of European interference.

Negative view

In the 18th century, racist views of Africa were most famously expressed by the Scottish philosopher David Hume: “I am inclined to suspect the negroes of being naturally inferior to the whites. There was scarcely ever a civilised nation of that colour, nor any individual, eminent either in action or speculation. No ingenious production among them, no art, no science.’

While some changed slightly over time, there were still some who continued to hold these derogatory views. In the 19th century, the German philosopher Hegel simply declared: “Africa is no historical part of the world.” Later, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Regius Professor of History at Oxford University, openly expressed the racist view that Africa has no history, as recently as 1963.

Early achievements

We now know that far from Africa having no history, it is almost certain that human history actually began there. All the earliest evidence of human existence and of our immediate hominid ancestors has been found in Africa. The latest scientific research points to the fact that all humans probably have African ancestors.

Africa was not only the birthplace of humanity, but also the cradle of early civilisations that made an enormous contribution to the world and are still marvelled at today. The most notable example is Kemet – the original name for ancient Egypt – which first developed in the Nile Valley more than 5,000 years ago and was one of the first monarchies.

But even before the rise of Egypt, an even earlier kingdom was founded in Nubia, in what is today Sudan. Ta Seti is believed to be one of the earliest states in history, the existence of which shows that thousands of years ago, Africans developed some of the most advanced political systems anywhere in the world.

Egypt

Kemet, more commonly referred to as Egypt of the Pharaohs, is best known for its great monuments and feats of architecture and engineering, such as the planning and construction of the pyramids, but it also made great strides in many other fields.

The Egyptians produced early types of paper, developed a written script and devised a calendar. They made important contributions in various branches of mathematics, such as geometry and algebra, and it seems likely that they understood and perhaps invented the use of zero. They also made important contributions to mechanics, philosophy and agriculture, especially irrigation.

In medicine, the Egyptians understood the body’s dependence on the brain more than 1,000 years before Greek scholars came up with the same idea. Some historians now believe that Egypt had an important influence on ancient Greece, pointing to the fact that Greek scholars such as Pythagoras and Archimedes studied there and that the work of Aristotle and Plato was largely based on earlier Egyptian science. For example, what is commonly known as the Pythagorean theorem was well known to the ancient Egyptians hundreds of years before Pythagoras’ birth.

The rise of Islam

The continent continued on its own path of development without major external intervention except for the Arab invasions of North Africa that began after the rise of Islam in the mid-7th century. These invasions and the introduction of Islam served to integrate North Africa, as well as parts of East and West Africa, more fully into the Muslim-dominated trading system of that period and generally enhanced the local, regional and international trade networks that were already developing across the continent.

Although sometimes spread by military means, Islam’s expansion was often facilitated by trade and the desire of African rulers to use Islamic political and economic institutions. The Arabic language also provided a script that aided in the development of literacy, book-based learning and record keeping.

The Songhay Empire – which stretched from present-day Mali to Sudan – was known for, among other things, the famous Islamic University of Sankoré based in Timbuktu, which was established in the 14th century. The works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle were studied there, as well as subjects such as law, various branches of philosophy, dialectics, grammar, rhetoric and astronomy. In the 16th century, one of its most famous scholars, Ahmed Baba (1564-1627), is said to have written more than 40 major books on subjects such as astronomy, history and theology and had a private library holding over 1,500 volumes.

One of the first reports of Timbuktu to reach Europe was by the North African diplomat and writer Leo Africanus. In his book Description of Africa, published in 1550, he says of the city: ‘There you will find many judges, professors and devoted men, all nicely maintained by the king, who hold scholars in great honour. There they also sell many handwritten North African books, and more is said to be made from the sale of books there than from any other trade.”

The North African, or Moorish, invasion of the Iberian Peninsula and the founding of the state of Córdoba in the 8th century had begun the reintroduction of much of the learning of the ancient world to Europe through translations into Arabic of works in medicine, chemistry, astronomy, mathematics and philosophy, as well as through the various contributions made by Islamic scholars. Arabic numerals based on those used in India were also transplanted, helping to simplify mathematical calculations.

This knowledge, brought to Europe mainly by the Moors, helped create the conditions for the Renaissance and the eventual expansion of Europe overseas in the 15th century.

Slavery in Africa

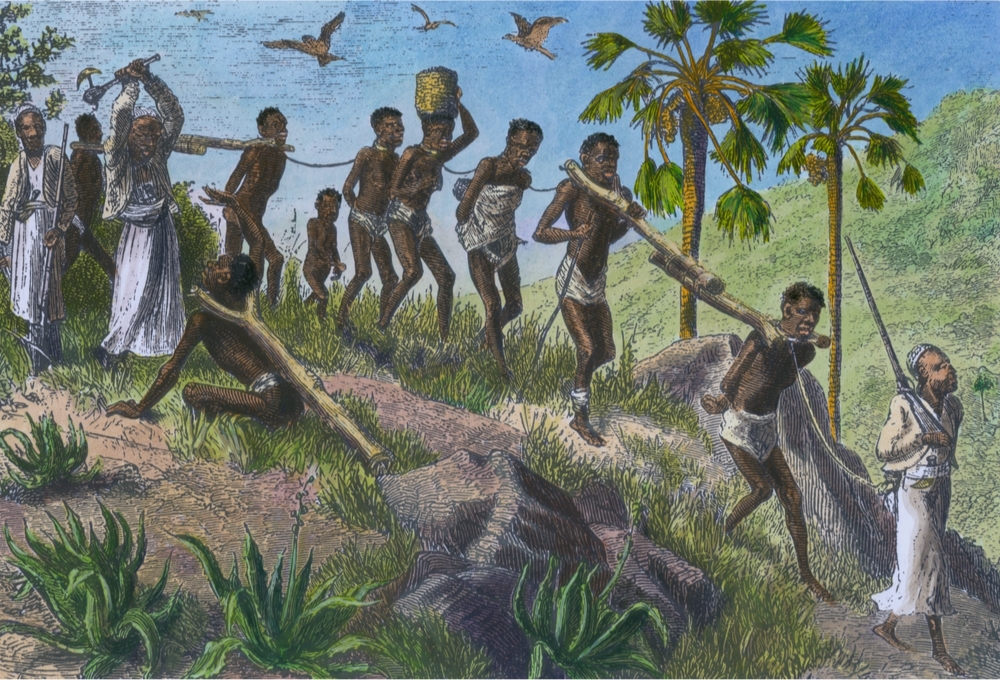

Between the 7th and 15th centuries, the external Muslim trade demand for African goods also included a demand for prisoners.

Forms of slavery have existed on every continent at different times in history – for example, as a means of exploiting those taken in war – especially where there was a shortage of labour and an abundance of land. Slavery was certainly present in some African societies before the rise of Islam. In ancient Kemet, for example, there are descriptions of European slaves being stamped. Later, in other African societies, especially those that were powerful states, slaves or unfree people could be found, although their status was generally little different from that of poor peasants. In fact, it may have been similar to that of serfs in medieval Europe, who were required to produce an agricultural surplus or perform other tasks for a particular ruler.

But when an external demand for slaves arose, there were some African communities that could and did supply slaves. For example, there was an export “trade” in slaves, taking them across the Sahara from West to North Africa, following a similar route to other commodities, such as gold and salt. Enslaved Africans were also forced to go to parts of the Middle East, to India and perhaps even as far as China. The most famous slave of East African origin is Malik Ambar (1549-1626) who was born in what is now Ethiopia. Enslaved at an early age, he eventually became the ruler of the Indian kingdom of Ahmednagar, famous for its military campaigns against the Mughals.

The development of states in Africa increased levels of inequality – between men and women, rich and poor, free and servile. In fact, inequality and economic exploitation were particularly prevalent in some of the most powerful and developed states, such as the Ethiopian Empire. In fact, historians generally consider Ethiopia to be a feudal society with many features similar to feudalism in Europe – that is, economic and political power was based on land ownership and the exploitation of those forced to work on that land.

Trading systems and gold

nn18213 Before 1600, a massive regional and international trading system stretched from the coast of West Africa, across the Sahara to North Africa and beyond. It was sustained by the extraction of gold in West Africa, as well as the production of many other goods there. For many centuries it was dominated by powerful empires such as Ghana, Mali and Songhay, which often controlled both the gold production and the major trading cities on the southern edge of the Sahara.

An 8th century historian wrote: ‘The king of Ghana is a great king. In his territory there are gold mines.’ When al-Bakri, the famous historian of Muslim Spain, wrote about Ghana in the 11th century, he reported that its king ‘rules a vast kingdom and has great power’. He was also said to have an army of 200,000 men and to rule over an extremely rich trading empire.

In the 14th century, the West African empire of Mali, which was larger than Western Europe, was reputed to be one of the largest, richest and most powerful states in the world. The Moroccan traveller Mohammed Ibn Batuta, when giving his very favourable impressions of this empire, reported that he had found “complete and general security” there. When the famous Emperor of Mali, Mansa Musa, visited Cairo in 1324, it was said that he brought with him so much gold that the price dropped dramatically and had not recovered its value even 12 years later.

It was gold from these great empires in West Africa that led to the early Portuguese exploration voyages.

Traditional societies

In the centuries before 1500, some of the world’s other great civilisations, such as Kush (in today’s Sudan), Axum (in today’s Ethiopia) and Great Zimbabwe, flourished in Africa.

But although the continent’s history before the transatlantic slave trade is often seen as one of great empires and kingdoms, many of its inhabitants lived in societies without a large state apparatus. They were often governed by councils of elders or by other kinship or age-based institutions. Religious and philosophical beliefs centred on maintaining communication with ancestors who could intercede with gods on behalf of the living and ensure the smooth functioning of society. (The Ethiopian Empire was unusual in that the Orthodox Christian Church, which was of ancient origin, performed increasingly important state functions.)

Many of these communities were small-scale, busy with farming, herding and producing enough from agriculture to survive and exchange at local markets. They could also be part of larger empires and, as such, were expected to produce a surplus or perform other tasks for an overlord. In short, while these societies varied greatly and were governed in different ways, they all developed according to their own internal dynamics.

The Igbo people, who still live in Nigeria, are an example of a society that was not part of a centralised state. They governed themselves in village communities that at different times used slightly different political systems. As in many other African societies that used similar methods, everyone was taught rules and responsibilities according to age and groupings – men or women together in age sets – that cut across family or village loyalties. Sometimes the extended family was responsible for organising and training people and for liaising with other similar extended family groups, through the advice of elders or elected chiefs. Therefore, relationships based on age and kinship were often very important.

Even societies that had kings and more centralised political structures also used these other political institutions and ways of organising people. What is important about them is that they involved many people in the decision-making process and in that sense were African forms of participatory democracy. Religious ideas generally supported and underpinned these systems of governance and, most importantly, gave people their own specific ways of understanding the world and the rules of their own society.

At the height of the transatlantic slave trade

In most parts of Africa before 1500, societies had become highly developed in terms of their own history. They often had complex systems of participatory government, or were established powerful states that covered large territories and had extensive regional and international connections.

Many of these communities had solved difficult agricultural problems and had come up with advanced techniques for the production of food and other crops and were engaged in local, regional or even international trade networks. Some peoples were skilled miners and metallurgists, others great artists in wood, stone and other materials. Many of the communities had also accumulated a large stock of scientific and other knowledge, some of it stored in libraries such as those in Timbuktu, but some passed down orally from generation to generation.

There was great diversity across the continent and therefore societies at different stages and levels of development. Most importantly, Africans had established their own economic and political systems, their own cultures, technologies and philosophies that had enabled them to make spectacular advances and important contributions to human knowledge.

The significance of the transatlantic slave trade is not just that it led to the loss of millions of lives and the departure of millions of those who could have contributed to Africa’s future, although depopulation had a major impact. But equally devastating was the fact that African societies were disrupted by the trade and increasingly unable to follow an independent path of development. Colonial rule and its modern legacy have been a continuation of this disruption.

The destruction of Africa through transatlantic slavery was accompanied by the ignorance of some historians and philosophers to nullify the whole story. These ideas and philosophies suggested that Africans, among others, had never developed any institutions or cultures, nor anything else of value, and that future progress could only happen under the leadership of Europeans or European institutions.

Related Posts

-

The Great Libraries of Africa — Then and Now

From ancient manuscript troves to modern digital hubs, Africa’s libraries have long been crucibles of…

-

How Africa Shaped the Ancient World: Trade, Gold, and Influence

Africa’s ancient kingdoms fueled global trade, pioneered ironworking, and exchanged ideas with Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and…

-

The Forgotten kingdoms of the Sahel: Ghana, Mali, and Songhai’s empires of gold and learning

From the 8th to the 16th centuries, the wide grasslands and deserts of the Sahel…