How four decades of reform — from milk-for-all to CBE — built today’s learning revolution and the millennial generation driving Kenya’s civic awakening.

The Classroom That Built a Nation

In the 1980s, every Kenyan child could count on one thing at breaktime: a packet of Maziwa ya Nyayo. The state-funded milk program under President Daniel arap Moi was more than a nutrition scheme it was a social contract. In public schools from Kisii to Turkana, it symbolized equality: the idea that every child, regardless of tribe or income, deserved a fair shot at learning.

Decades later, that generation’s children are the millennials who filled Kenya’s streets in the 2025 protests digitally literate, civically assertive and products of one of Africa’s most ambitious education systems. Their competence is no accident. It is the legacy of sustained policy evolution from Moi’s social populism, through Kibaki’s investment in free primary education, to Ruto’s re-engineering of competency-based learning for a new labor economy.

How Presidents Shaped Kenya’s Learning Landscape

Jomo Kenyatta (1963-1978):

Focused on Africanization and expansion. His administration built the first wave of national schools and teacher training colleges, framing education as a nation-building tool.

Daniel arap Moi (1978-2002):

Introduced the 8-4-4 system in 1985 — eight years primary, four secondary, four university — to blend academics with practical skills. His “Maziwa ya Nyayo” program and school infrastructure boom extended access but also cemented exam-centered culture and rote learning.

Mwai Kibaki (2003-2013):

Launched Free Primary Education (FPE) in 2003, enrolling over 1.5 million new pupils in a year. His administration’s focus on ICT, teacher incentives, and secondary expansion produced a generation with better literacy, numeracy, and digital readiness — today’s millennial workforce and activist base.

Uhuru Kenyatta (2013-2022):

Pioneered the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC), shifting from content memorization to applied skill. Introduced the Digital Literacy Program (2016), delivering laptops and digital content to primary schools.

William Ruto (2022–):

Renamed and refined CBC into Competency-Based Education and Training (CBE/CBET), aligning schooling directly with the labor market. His focus on TVET, apprenticeship models, and employer engagement seeks to make education the engine of industrial transformation.

2025: The Year of Competency Assessment

2025 marked a turning point. Over 1.1 million learners sat the Kenya Junior School Education Assessment (KJSEA) — the country’s first nationwide test under CBE pathways. The KJSEA replaced rote recall with portfolio assessment, group projects, and continuous evaluation. But it also raised difficult questions:

- How will results translate into senior-school placements?

- Can they be compared to KCPE scores?

- Are teachers ready for the shift from summative grading to competency rubrics?

For parents, the anxiety is palpable. Placement into senior-school specialisations academic, technical, or TVET determines future opportunities. The transition requires clear guidelines and transparent criteria.

From CBC to CBE/CBET: What It Really Means

While CBC grabbed headlines, the real structural shift came with new terminology:

Competency-Based Education (CBE) and Competency-Based Education and Training (CBET).

This rebranding signals tighter integration between general education and vocational training.

Under the new model:

• Grade 10 learners select one of three pathways: academic, technical and vocational, or sports/arts.

• TVET institutes, polytechnics, and secondary schools share curricula and certification systems.

• Assessment rubrics are tied to employability metrics rather than exam scores.

This is Kenya’s quiet revolution — retooling the education pipeline to feed real industries: construction, ICT, health, agribusiness, and creative economies.

Foundations First: ECDE and Language Policy

Every competency journey starts with play. Kenya’s 46,000 Early Childhood Development and Education (ECDE) centers serve over 3 million learners, yet quality varies sharply across counties.

Devolution gave counties responsibility for ECDE staffing and pay a progressive move that also widened inequality. Wealthier counties like Kiambu or Nyeri retain trained teachers on payrolls; poorer ones struggle with contract workers and bare classrooms.

The language of instruction debate runs through these early years. Policy dictates mothertongue teaching up to Grade 3, then a shift to English and Kiswahili. But in Nairobi’s multilingual settlements, which “mother tongue” applies? Some teachers mix languages to aid comprehension, while others stick to English for exam alignment. The policy’s uneven rollout affects literacy outcomes a key CBC metric.

Teachers: The Binding Constraint

No reform survives a teacher shortage. Kenya needs roughly 24,000 new teachers for the Grade 10 transition alone. The Teachers Service Commission has struggled to match recruitment targets, while continuous professional development (CPD) on competency assessment lags behind. Teachers also face heavier administrative loads, documenting learner progress, designing performance tasks, and managing digital submissions.

As one union leader quipped during a 2024 strike: “We support reform, but not unpaid reform.” Without sustained CPD, incentives, and manageable class sizes, even the best curriculum remains theory.

Digital Divide and Learning Platforms

Competency learning thrives on connectivity but access remains patchy. In October 2025, Airtel Kenya announced free access (zero-rating) to the Kenya Education Cloud and Elimika teacher training portal, cutting data costs for teachers and schools. Yet national device ownership remains in the single digits, and less than 30% of households have internet access.

Digital learning is therefore stratified: private schools and urban public schools surge ahead; rural institutions lag. The dream of equal opportunity depends not only on content but on hardware, bandwidth, and electricity.

TVET, Apprenticeships and the World of Work

Kenya’s CBE framework aims to correct a long-standing mismatch: graduates without practical skills. Under the new pathways, senior-school and TVET students pursue specializations in mechatronics, hospitality, construction, ICT, or agro-processing. Industry councils now codesign curricula, while employers host apprenticeships.

This shift positions Kenya to build a competent workforce, not just credentialed one. As one policy analyst notes, “Ruto’s education bet is on employability — not just employability abroad,but home-grown innovation.”Equity and Special Needs: The Inclusion Gap

About 260,000 learners are officially registered with disabilities but experts say the real number is double.

The country has fewer than 2,500 special units and limited adaptive resources. “Itinerant” special-needs teachers exist on paper but are rarely deployed.

CBC promises inclusion, but without investment in Braille materials, hearing devices, or accessible infrastructure, it risks exclusion by another name.

An inclusive CBE system must move from rhetoric to resourcing.

Counties, Devolution and Inequality

Devolution was meant to localize equity; instead, it sometimes magnified disparities. Counties manage ECDE, infrastructure, and feeding, yet resource allocations differ drastically. A pupil in Nyeri or Kisumu may have double the facilities of one in Marsabit or Tana River. National equalization funds and conditional grants remain inconsistent limiting the reach of reform.

School Feeding and Social Protection

From Maziwa ya Nyayo to the 2023 National School Meals Strategy, the link between nutrition and learning endures.

The goal: feed 10 million learners by 2030, expanding into arid regions and informal settlements.

Yet coverage remains partial, especially where counties rely on NGO support.

Feeding is not just a welfare issue it’s an education policy lever. A hungry learner cannot internalize competencies.

Money, Markets and Reform Fatigue

CBE’s rollout is expensive.

• Teacher wage bill: ~KSh 400 billion annually

• TVET infrastructure expansion: KSh 60 billion (2024–2029)

• Digital devices and training: ongoing procurement and maintenance costs

Every shilling spent on workshops or tablets competes with hiring more teachers. Fiscal oxygen is limited.

Audits of the earlier Digital Literacy Program exposed procurement inefficiencies a cautionary tale as Kenya scales up again.

Private Schools, Coaching and Inequality

Private academies remain powerful adapting fastest to CBE thanks to resources and smaller classes.

Meanwhile, a new coaching industry has sprung up around CBC project work and assessments, echoing KCPE-era exam drilling.

Unless public schools receive equitable resourcing and clear guidelines, the “competency gap” may replace the “exam gap.”

Data, Accountability and Learning Outcomes

Policy is not performance.

Independent assessments (Uwezo, KNEC) show literacy and numeracy stagnation in lower grades. Without measurable outcomes, reform becomes political theatre.

The release of the 2025 KJSEA results will be a test not only of students but of credibility. Public trust hinges on transparent reporting and clear evidence that the competency model actually improves learning.

Human Story: The New Competency Learner

In Nakuru County, 14-year-old Wanjiku Kamau faces her first KJSEA. She dreams of studying mechatronics in the technical pathway.

Her father worries about costs, but her teacher insists the new system finally rewards skill and curiosity, not just memory.

“I want to build things,” she says, “not just pass exams.”

Her words capture the spirit of a nation trying to learn differently — and to live differently.

Conclusion: The Competency Generation

Kenya’s education story is one of reinvention from milk to machines, from memory to mastery. Each era built on the last: Moi fed bodies, Kibaki expanded minds, Uhuru rewired the system, and Ruto is aligning it with the economy.

The 2025 generation, schooled under CBC and CBE, are not passive recipients; they are civic actors, digitally fluent, and demanding accountability in streets, classrooms, and offices alike.

Education remains Kenya’s loudest mirror. And in that reflection, the question is no longer whether children are in school, but whether school is in them equipping them not just to pass, but to build.

Quick Context Box: Kenya’s Education Evolution

Milestone Year Key Policy Impact

- Maziwa ya Nyayo introduced 1980 Expanded access and nutrition under Moi

- Free Primary Education 2003 1.5M new enrollees under Kibaki

- CBC rollout 2017 Shift to skills and continuous assessment

- CBE/CBET policy launch 2024 Labour-market alignment

- KJSEA first national assessment 2025 1.1M learners assessed under new model

“We support reform — but not unpaid reform.” — Teacher union leader, 2024.

“I want to build things, not just pass exams.” — Wanjiku Kamau, student.

“Reform ambition is high, but fiscal oxygen is low.” — Policy analyst.

Related Posts

-

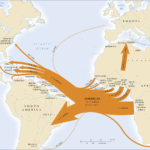

The Slave Trade’s Lesser‐Known Routes: From East Africa to the Middle East

Beyond the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean slave trade uprooted an estimated 4–6 million Africans over…

-

From the Sahara to the Cape: Africa’s Most Scenic Road Trips

Discover Africa's most breathtaking road trip routes from Morocco’s Atlas Mountains to South Africa’s Cape…

-

500 Kenyans Removed from the Wealth List

Five hundred Kenyans were dropped from the exclusive list of dollar millionaires in 2023. This…