Explore the untold story of the 1953 Tumutumu Hills battle, where Mau Mau generals China, Kariba, and Tanganyika fought near Mount Kenya for Kenya’s freedom.

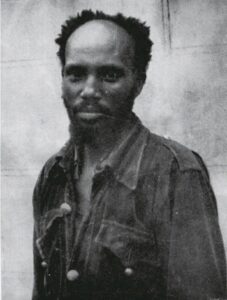

November 1953, the montane forests on the eastern slopes of Mount Kenya filled with the sound of battle. On a ridgeline known locally as the Tumutumu Hills, roughly four miles east of Karatina on Mount Kenya’s eastern slopes, Mau Mau units led by Waruhiu Itote (General China) and commanders known as Kariba and Tanganyika clashed with an advancing column of colonial security forces.

What followed was a fierce, chaotic daytime engagement, a tactical withdrawal under fire that became, in local memory, proof of the insurgents’ resilience an important symbolic moment.

A Challenge in the Heart of Kikuyu land

Karatina at that time served as a divisional administrative and garrison centre, functioning as a supply hub for patrols extending into the Mount Kenya forest. Its position on the Nairobi–Nyeri corridor made it vital to the colonial counterinsurgency network, ensuring the steady movement of troops, rations, and intelligence. To menace or move on Karatina was therefore to challenge the security core of the White Highlands, a region where fertile land had been alienated for settler agriculture and placed under tight military surveillance. For the Mau Mau, striking so close to this frontier of settler power was both a symbolic rejection of colonial land control and a strategic demonstration that the heart of Kikuyu land was not subdued.

The Night Before Battle

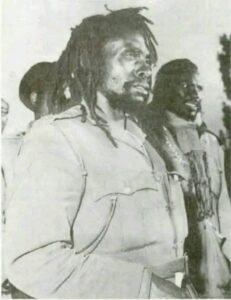

Beneath the dense canopy near Kirimukuyu and Tumutumu Mission, fighters gathered and prepared. The leadership included Itote — whose frontline discipline and calm authority made him a natural rallying point — alongside Kariba and Tanganyika, regional commanders whose noms de guerre echo through oral histories of the Mount Kenya campaign.

Tension ran high but the purpose ran deeper. Fighters sharpened blades, checked ammunition, and organized food caches. Civilians, especially women and children, acted as lookouts and messengers. One enduring story recalls a young scout named Kanguniu creeping through darkness at dawn to warn that security forces were closing in — a moment emblematic of the quiet heroism of local auxiliaries.

Intelligence, Disguise and a Risky Probe

Fieldcraft and disguise were staples of Mau Mau warfare. According to veteran testimony, General China dispatched Faranja, a trusted scout, to gather intelligence disguised as a woman. Moving through checkpoints, Faranja confirmed that the enemy’s cordon was tightening. Such small acts of deception often determine whether a column held its ground or melted away before being trapped.

Weapons and Readiness

Veteran accounts place the gathering at several hundred to a thousand including auxiliaries; active combatants were likely fewer. Their weaponry was mixed: bolt-action and semi-automatic rifles, Sten and Bren guns where available, grenades, and pistols far fewer than their opponents possessed. Yet terrain familiarity and fluid movement gave them a tactical advantage in the forests’ thick cover.

Fire in the Forest

At first light, the Mau Mau opened fire with a concentrated volley meant to fracture the encircling line. The initial grenades and rifle bursts ripped through the still morning air. “There was so much gunfire that the trees and green leaves caught fire,” one survivor later said. Smoke rose through the canopy; tracer rounds set dry leaves alight; and the echoes of Bren guns rolled down the valleys. For over an hour, the hills roared.

Colonial reinforcements, police contingents, King’s African Rifles detachments, and local Home Guard units returned fire with heavier weapons. Aircraft circled and dropped 3- to 5-pound bombs, but dense foliage blunted their impact. Few if any Mau Mau were killed by the bombing; most casualties on both sides came from close-quarters ground fire.

Breakout and Withdrawal

Pinned and partially encircled, China’s men fought a disciplined withdrawal toward Rui Ruiru. It was no route but a calculated escape under pressure. Reinforcements from Kiamachimbi, Nyeri, and Nanyuki closed in, triggering renewed clashes across neighboring ridges. By nightfall, small groups had slipped through side valleys and regrouped in secondary hideouts. The Mau Mau survived, bloodied but intact.

Casualty figures remain disputed: colonial reports claimed minimal insurgent losses, while oral accounts speak of several dozen killed or wounded on both sides. Archival verification will help establish a credible range. Some accounts suggest that General Kariba sustained minor injuries during the withdrawal and became separated from the main column, though he later rejoined surviving units.

For local communities, Tumutumu became a moral victory proof that even against artillery, aircraft, and tanks, the forest could protect its own.

Aftermath and Significance

Tumutumu’s immediate tactical result was mixed: the security forces asserted temporary control of the ridgeline and surrounding approaches, but the guerrillas maintained their organizational capacity and continued operations in the region. In the days that followed, local civilians bore the brunt of collective punishment — curfews, intensive village searches, detentions, and food-control restrictions tightened around Kirimukuyu and Karatina. These measures reflected a broader shift toward the “protected village” or villagization policy, which forced the relocation and screening of rural populations in fortified settlements to cut off the Mau Mau’s forest supply lines.

Veterans later recalled Tumutumu as proof of endurance. One Nyeri elder, interviewed decades later, put it simply: “They said we were trapped — but the forest opened and let us live.”

The battle also influenced subsequent security deployments across Central Province. Archival patterns suggest an uptick in patrol density, new blockhouses along forest margins, and tighter coordination between Home Guards and the King’s African Rifles — developments that would define counterinsurgency in the Mount Kenya sector through 1954 and beyond (to be confirmed through military archives).

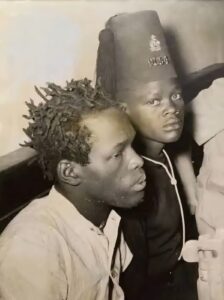

Waruhiu Itote’s later capture on January 15th 1954 and subsequent negotiations with the colonial authorities complicated his postwar reputation; some valorized his battlefield leadership, while others critiqued his cooperation after capture. Yet in Karatina and neighboring settlements, the memory of Tumutumu endured — a story of forest flames and unbroken spirit woven into veterans’ narratives, funerary commemorations, and local oral histories.

Legacy and Reflection

Tumutumu was more than a battle, it was a social watershed. For villagers, it marked the tightening of the Emergency regime; for fighters, a test of endurance; and for future generations, a legend of courage and defiance. Any modern commemoration must hold this complexity together: resistance, survival, and the blurred line between battlefield and home.

The Battle of Tumutumu Hills reminds us that Kenya’s road to independence was forged not only in famous declarations and prisons, but also in hidden valleys and burning forests — in places where ordinary people, armed with faith and grit, stood their ground against an empire. In Tumutumu’s smoke and silence, the struggle for freedom took root, leaving a legacy that still whispers through the trees of Mount Kenya.

Related Posts

-

The Forgotten kingdoms of the Sahel: Ghana, Mali, and Songhai’s empires of gold and learning

From the 8th to the 16th centuries, the wide grasslands and deserts of the Sahel…

-

The Legacy of Queen Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba

Discover the story of Queen Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba the 17th-century African warrior queen…

-

The Battle of Isandlwana and the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879

At eleven o'clock on the morning of 22 January 1879, a troop of British scouts…