Food preservation is one of humanity’s oldest arts and one of its most powerful storytellers. In Norway, Arctic winds sweeping over the Lofoten Islands have dried cod into stockfish for more than 1,000 years. Hung on wooden racks and cured by cold air, the fish keeps for years without salt or refrigeration, becoming concentrated in flavor and dense in protein.

Thousands of kilometers away, Africans were also drying, smoking, and salting fish long before contact with Europe. Tilapia sun-dried on lake shores, bonga split and salted for West African markets, catfish smoked over smoldering wood these were not just techniques of survival, but flavors people came to prize. That’s why, when Norwegian stockfish arrived through trade in the 19th century, it did not land as a stranger. It was a familiar idea in a new form: preservation as taste, survival as delicacy.

Stockfish Meets African Ingenuity

By the 19th century, stockfish was moving steadily into West Africa through European trade routes. Its story deepened during the Biafran War (1967–1970), when blockades starved southeastern Nigeria. Stockfish became a lifeline protein, and ever since, it has been folded deeply into Nigeria’s culinary identity.

Today Nigeria is the largest importer of Norwegian stockfish, with millions of kilos arriving annually. Known locally as okporoko in Igbo, it carries prestige in soups such as egusi, ogbono, and ofe onugbu (bitterleaf soup). To serve a guest plenty of stockfish is to show wealth and generosity; hosts sometimes boast about the size and tenderness of the pieces in their pot.

In Ghana, stockfish enriches light tomato-based soups eaten with fufu. In Angola and Mozambique, it fuses with peri-peri chilies, coconut milk, and palm oil, echoing both Portuguese bacalhau traditions and African spice. In Cape Verde, it links directly to Lusophone bacalhau but swaps cassava, beans, or plantains for potatoes, indigenizing the dish.In East Africa, stockfish joined coconut stews and groundnut sauces, fitting easily into preservation cultures that already valued smoked tilapia or sardines. Its chewy umami bite resonated with local palates that already knew the beauty of dried fish.

Why Stockfish Felt at Home in Africa

Three reasons explain why stockfish thrived so quickly:

- Resonance of Preservation – Africans prized the smoky chew of dried catfish, just as Norwegians prized the concentrated umami of stockfish. Preservation had already shaped taste itself.

- Texture & Depth – Its firm chew and deep savor complemented vegetable stews and starches like yam, fufu, cassava, and rice.

- Symbol of Abundance – Imported and relatively costly, stockfish became a status ingredient — a food of weddings, Sunday feasts, and festivals.

Nutrition & Practical Wisdom

Stockfish is not just symbolic — it is one of the world’s most nutrient-dense foods:

- 80% protein by weight, with all essential amino acids.

- Very low in fat, making it lean but filling.

- Rich in vitamin B12, calcium, and iron, supporting blood health and bone strength.

- Naturally preserved without additives — and can last years if stored dry.

Africans also developed kitchen wisdom around it. Soaking stockfish in warm water (sometimes with a splash of milk or baking soda) softens it faster and mellows its strong aroma. Heads and bones are simmered into broth, ensuring nothing goes to waste.

Recipe: Nigerian Stockfish Egusi Soup

Ingredients

- 200 g stockfish (soaked overnight to soften)

- 200 g beef or goat meat (optional)

- 1 cup ground egusi (melon seeds)

- 1 medium onion (chopped)

- 2 fresh tomatoes or 1 cup tomato purée

- 2 tbsp ground crayfish

- 2–3 fresh chilies (or to taste)

- ½ cup palm oil

- 3 cups spinach or ugu leaves (washed and chopped)

- 2 stock cubes or bouillon powder

- Salt to taste

Method

- Prepare stockfish: Soak overnight. Drain and cut into bite-sized pieces.

- Cook meat and stockfish: In a large pot, simmer beef/goat with onion, salt, and stock cubes until tender. Add stockfish and cook for another 10 minutes.

- Make the egusi paste: Mix ground melon seeds with a little water to form a thick paste.

- Build the soup: Heat palm oil in a pan, add tomato, onions, and chilies. Fry until fragrant. Stir in egusi paste, cooking gently until it forms a thick, grainy texture.

- Combine: Add the fried egusi mix into the stockpot with meat and stockfish. Stir well.

- Add crayfish, adjust seasoning, and simmer.

- Finish: Add spinach/ugu leaves and cook briefly until wilted. Serve hot with pounded yam, fufu, or rice.

Final Reflection

Stockfish in African kitchens is more than an ingredient; it is a culinary handshake across climates and centuries. From the icy racks of Lofoten to Lagos’ bustling markets, from Cape Verdean feasts to Mozambican curries, it embodies resilience, adaptation, and memory.Both Norwegians and Africans transformed necessity into flavor, and flavor into identity. Today, every pot of egusi, light soup, or coconut curry seasoned with stockfish carries not just taste, but history proof that preservation is not only survival, but a shared heritage.

Related Posts

-

Markets of Africa: Where to Buy Authentic, Handmade Treasures

Explore Africa’s vibrant markets and discover authentic, handmade treasures from Ghana’s royal Kente to Tuareg…

-

Equinor Pays More in Taxes to Africa Than Norway Gives in Aid

Norway’s total aid to Africa is small compared to the amount paid by the state-owned…

-

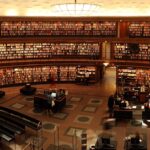

The Great Libraries of Africa — Then and Now

From ancient manuscript troves to modern digital hubs, Africa’s libraries have long been crucibles of…